A few too many drops of insulin and you can go unconscious. It seems crazy then, that once diagnosed with type 1 diabetes you are bombarded with information and sent home, expected to self-administer insulin and manage your new medical condition. This is all the doctors can do though – although they’re always happy to help, it’s up to you to educate yourself and learn to live with T1D.

In previous posts, I’ve detailed some of the challenges of life with T1D. So what then does living with T1D involve on a daily basis?

There are many different types of insulin, each with distinct effects, including the speed at which it starts working in the body, its duration and its profile. Some analogues suit people better than others.

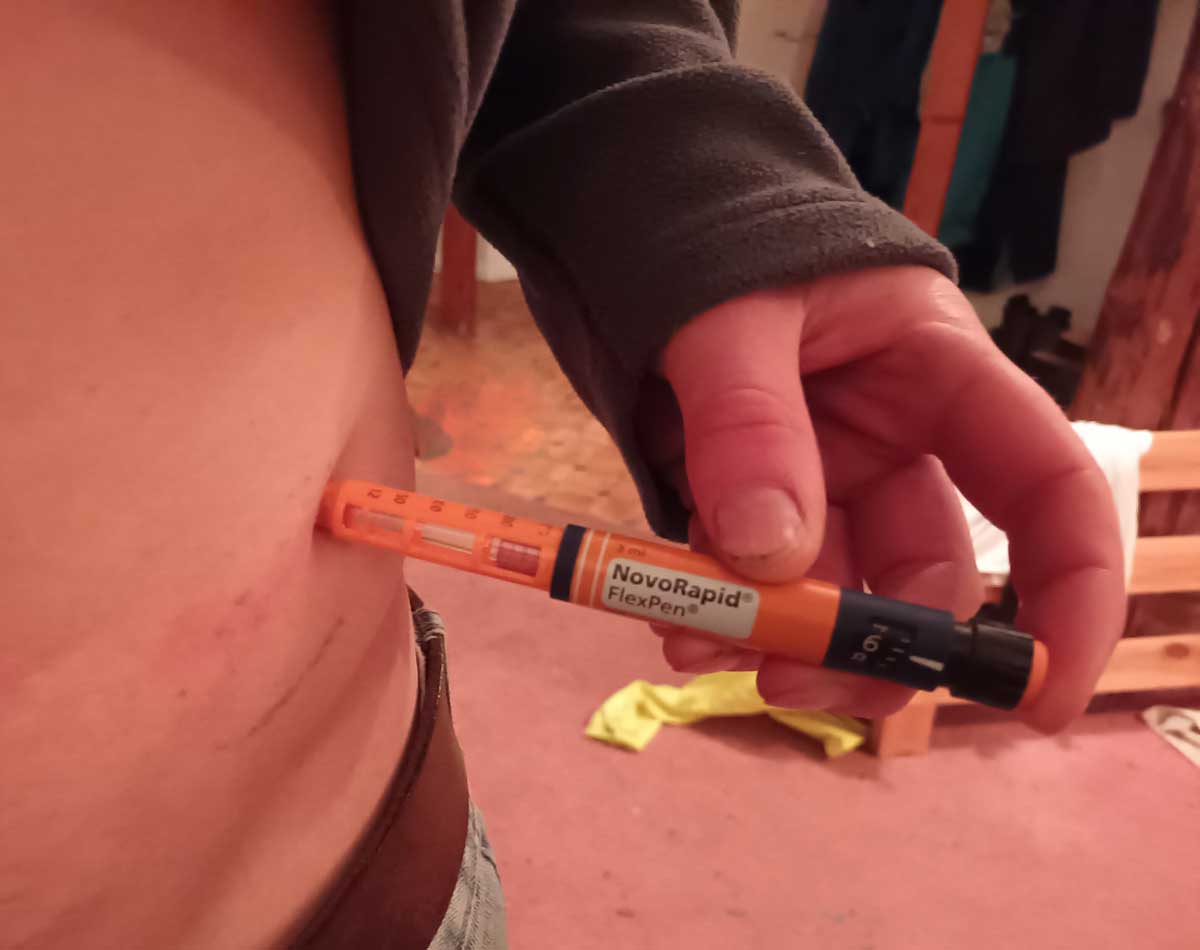

I inject 2 insulin analogues each day. Firstly a short-acting insulin – Novorapid (aspart) – that supposedly has an onset of 10–20 minutes, a maximum effect between 1 and 3 hours after injection and is effective for 3–5 hours. I use Novorapid to ‘cover’ carbohydrate intake and to correct high blood sugars. The second insulin is Levemir (detemir) – a long-acting insulin that supposedly has an onset of 2 – 4 hours, a maximum effect between 6 and 14 hours and is effective for up to 24 hours.

I say supposedly because everyone reacts differently and there are so many factors affecting insulin sensitivity, meaning no two days are the same. After exercise, for example, Novorapid starts working almost immediately due to rapid absorption from increased blood flow.

Insulin is injected subcutaneously into fatty tissue, typically on the abdomen. Some people do find needles painful and unpleasant, and it can be wearing having to stab yourself multiple times a day, but personally, this aspect doesn’t bother me.

Calculating doses of insulin is perhaps the trickiest part of daily life with T1D, since you are trying to replicate the job of a highly complex metabolic system. Injected insulin is a blunt instrument in comparison, and trying to take into account all of the factors affecting blood sugars is very difficult. A dosage error will lead to out of range blood sugars, which can be frustrating.

The only way to calculate the correct insulin dose is through trial and error and by keeping a diary and looking at historical data to find patterns. For rapid insulin dosage, a carbohydrate to insulin ratio can be calculated, so that for example for every 20 grams of carbohydrate you eat, you inject 1 unit of insulin.

Controlling some of the factors that influence blood sugars, like diet and exercise, can help too, but unfortunately, out of range blood sugars are just an inevitable part of life with type 1. At some stage you have to accept you have this disease, and your blood sugars aren’t going to be perfect.

Obviously, to control blood sugar levels, you first have to know what level you are on. A blood glucose meter gives a snapshot of your level at one time. This will tell you if you are high or low, but it won’t tell you what your trend is, unless you do a series of blood pricks.

Continuous glucose monitors (CGMs) solve this problem. A CGM is a sensor that transmits a blood glucose reading at regular intervals, usually every 5 minutes, meaning a blood glucose trend is easily seen and data is being recorded constantly, especially important while you sleep and exercise.

CGMs stick to the skin, usually on the abdomen, with a hair-like glucose sensor just under the skin. The sensor is a glucose oxidase coated microelectrode that continuously converts glucose from the liquid found between the cells of the body (interstitial fluid) into an electronic signal, the strength of which is proportional to the amount of glucose present.

CGMs can also be programmed to sound alarms for high and low levels. This is very helpful during exercise, when hypo unawareness is common, during the night, when you may sleep through hypoglycemia, and for people who have general hypo unawareness.

Of course, living with a CGM has its own drawbacks – they are not 100% reliable and can report false hypoglycemia or hyperglycemia. This leads to ‘alarm fatigue’ meaning people become desensitized or annoyed at unnecessary alarms and resort to turning the alarm off. Sometimes I’ll take the risk of high or low sugars rather than having a night of broken sleep, constantly being woken by alarms. In addition, CGMs are expensive, can cause skin irritation and can be knocked off. Despite this, I have found my CGM to be a game-changer and couldn’t recommend one enough.

I haven’t mentioned some other technology such as insulin pumps. I don’t use any of this for certain reasons which I’ll discuss in a future post!

Ultimately, good diabetes management requires a lot of hard work to try and understand your body. Controlling the factors that affect blood glucose levels and observing the effect is certainly helpful – carbohydrate intake, sleep, exercise etc – even if keeping diaries and weighing food is tedious. Some people try to keep these factors the same every day, and living in a regimented fashion certainly makes T1D management easier, since blood sugars levels are more predictable. This can be restrictive though, and cause problems when life throws a surprise.

Leave a Reply