While I don’t make long term plans for my trip, I don’t want it to seem like I have no regard for safety. Planning is obviously a crucial part of staying safe and I thought I’d share my process.

Safety starts before you get on the water – preparation and planning are key. Each evening on my trip, I planned the next day of paddling. I would look at the weather, wind and tide forecasts and the features of the coastline to build a prediction of what would likely happen – then there should be no surprises once at sea. I don’t like stopping to check maps and navigate once paddling, and I found that doing some planning allowed me to just get into the flow of paddling. Once at sea I’m just navigating by sight and following my compass, remembering what I’d planned the night before.

Here’s a made-up scenario from a section of Brittany coastline I paddled: let’s pretend my start point is Paimpol and I want to head West.

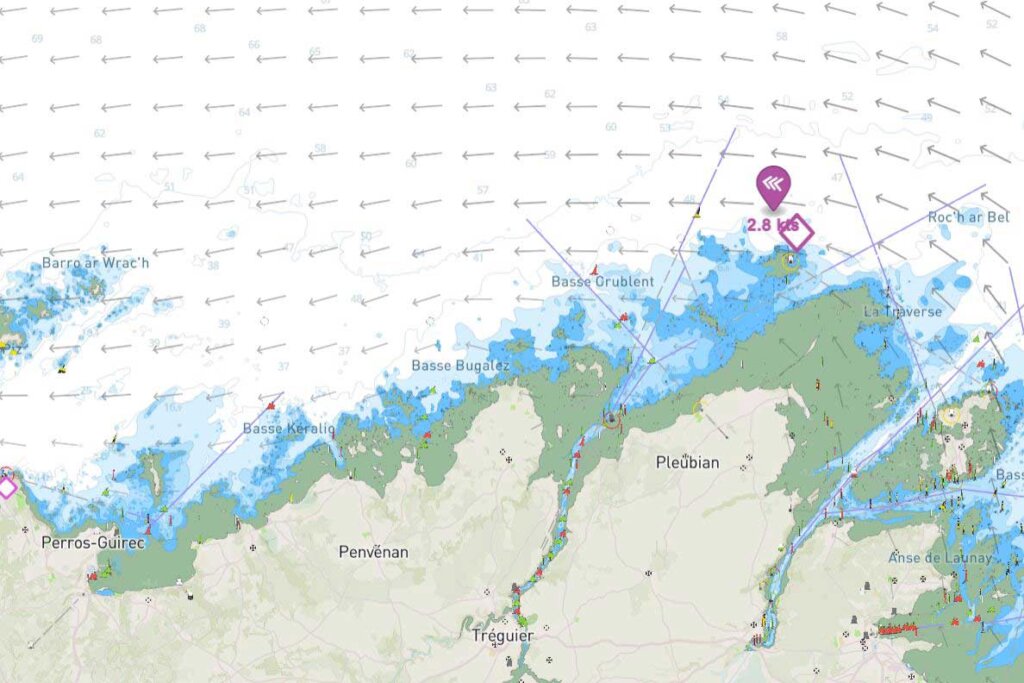

First I look at the tides – specifically the tidal stream maps on savvy navvy, not just the times of high/low water which don’t always correlate with the currents. This shows that the tidal streams start flowing West at around 8 am and continue until around 2 pm and that it is an 8-meter tide flowing at a peak of around 3 knots. I want to paddle with the tide and not against it, especially in this case when the current is strong, so must paddle in the 6-hour window between 8 am and 2 pm. After 2 pm the tide turns and will be against me. I will be arriving at my destination at low tide, so it’s also important to check how I can come ashore – an estuary may be full of waist-deep mud for example.

What about the wind? At 8 am it’s blowing Westerley at around 20 knots so unfortunately, it will be a headwind. It also means there will be wind-against-tide which produces steep, breaking waves. The wind is getting stronger throughout the day, and by 2 pm, it’s blowing at over 30 knots. This area of coast is exposed and there is a large fetch. This means a large swell is likely to have built, and this can be checked by looking at data from wave-buoys, if available.

How about the features of the coastline? Well, there are two large rivers entering the sea along my route, the current of these rivers may create some confused waters. Although my wind map doesn’t show it, it’s possible that wind may be funnelled down the river valleys too, as I found on day 42 when I got a taste of the Mistral blowing down the Rhone valley.

There are also several large headlands, where wind and tide are often accelerated and there may be a tidal rip [i]“agitation of water caused by the meeting of currents or by a rapid current setting over an irregular bottom“ or overfall [ii]“short, breaking waves occurring when a strong current passes over a shoal or other submarine obstruction or meets a contrary current or wind“. Even just waves reflected off the headland could create difficult conditions. There are also many islands, which can be difficult to navigate in rough conditions and suggest shallow depth which also creates bigger waves.

Another consideration is the weather – how cold is it? is there any risk of a thunderstorm? Could a fog descend? Also, when will it get dark and what is the water temperature? These bits of info all add up to help you assess the risk. Getting some local knowledge is always valuable too.

With all of this information, I can now estimate what speed I will paddle at and thus what distance I will cover in the 6 hours available. It takes experience to even make a rough estimate. I can also calculate what time I will reach certain features, and adjust my departure to pass them at the optimum time. For example, I may leave an hour before 8 am to reach a headland when the tidal flow is low and the overfalls are smaller.

On my trip, the destination each day is flexible – often I just see how far I get depending on how I feel and what the conditions actually are. But I always look at the possible end points and plan several escape routes for use in the event of a problem (blue dots on the map). A beach sheltered from the wind is preferable, and surf forecasts and webcams can be consulted to decide if a beach looks suitable for landing on.

In this scenario, I decide I should only paddle for 3 hours and be off the water before the wind picks up. At 10 km/h I can plan to travel 30km which takes me to Plougrescant. The 2 headlands marked with triangles are possible danger points and I don’t fancy it, I’ve planned escape routes to fall back on.

I’m not saying everyone should do it like this – it totally depends on your experience, where you’re paddling, who you’re paddling and loads of other factors. Paddling alone in a place I’ve never been before and having type 1 diabetes increases my risk so I do more planning than I would for a group paddle back home.

Good websites/apps

- SavvyNavvy

- Windy

- Imray tides planner

- iboating

- WindGuru

- Google maps/earth (very useful)

- Navionics

- C-map

- Magic seaweed

Leave a Reply